Augusta Christine Fells

Created monumental work The Harp for the 1939 New York World’s Fair Harlem Renaissance

In 1939, the artist Augusta Savage was the first African American woman to open her own art gallery in America, the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art which was devoted to showcasing the work of Black artists. Over 500 people poured into the opening reception, where Savage announced that “We do not ask any special favours as artists because of our race. We only want to present to you our works and ask you to judge them on their merits.”

Savage struggled through poverty and racism, she often didn’t have the funds to cast her sculpture in bronze, or the money to store them andmany were cast in plaster and painted with shoe polish to make them look like bronze.

Despite the fact her art gallery only functioned for a few months before it ran out of funding, she was keen on creating an infrastructure for Black artists, recognising the need for a network for African American artists to succeed. Savage once said that in all the African American homes she visited, only two had artworks by African American artists. She asked “How does the African American artist survive?” Augusta Savage put a lot of thought and energy into creating these intellectual spaces and networks for the work of Black artists.

Savage’s extraordinary career spanned the Depression era to the postwar period and she worked as an artist, educator and a trailblazer of African American arts.

1892

1962

Green Cove Springs, Florida

American

Grande Chaumiere, Paris, 1929

Salon d’ Automne, Paris, 1930

Argent Galleries, New York and Art Anderson Gallery, New York, 1932

Argent Galleries, New York and New York World’s Fair, 1939 New York Public Library, 1988

The career of Augusta Savage was fostered by the climate of the Harlem Renaissance. During the 1930, she was well known in Harlem as a sculptor, art teacher, and community art programme director.

Born Augusta Christine Fells in Green Cove Springs, Florida, on 29 February 1892, she was the seventh of fourteen children of Cornelia and Edward Fells. Her father was a poor Methodist minister who strongly opposed his daughter’s early interest in art.

In 1907 Savage married John T Moore, and the following year Irene, her only child, was born. Moore died several years after the birth of their daughter. Around 1915 the widowed artist married James Savage, a carpenter whose surname she retained after their divorce during the early 1920s. In 1923, Savage married Robert L Poston, her third and final husband, who was an associate of Marcus Garvey.

Savage’s father moved his family from Green Cove Springs to West Palm Beach, Florida, in 1915. Lack of encouragement from her family and the scarcity of local clay meant that Savage did not sculpt for almost four years. In 1919 a local potter gave her some clay from which she modelled a group of figures that she entered in the West Palm Beach County Fair. The figures were awarded a special prize and a ribbon of honour. Encouraged by her success, Savage moved to Jacksonville, Florida, where she hoped to support herself by sculpting portrait busts of prominent Blacks in the community. When that patronage did not materialize, Savage left her daughter in the care of her parents and moved to New York City.

Savage moved to New York on a scholarship to study art at the Cooper Union, where she completed a four year course in three years. In 1932 she won a scholarship to study at the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in France, but the French government retracted her admission after learning she was Black. A typewritten letter from the admissions committee said that “it would not be wise to have a coloured student … as complications would arise, and the student would suffer most from these complications.”

. “She alerted the press, [and] it made headlines,” said Wendy Ikemoto, curator of a 2019 exhibition of her work at the New York Historical Society. “As a Black woman during the Jim Crow era in the 1920s, it was really extraordinary.”

During the mid1920s when the Harlem Renaissance was at its peak, Savage lived and worked in a small studio apartment where she earned a reputation as a portrait sculptor, completing busts of prominent personalities such as W E B Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. Savage was one of the first artists who consistently dealt with Black physiognomy. Her best known work of the 1920s was Gamin, an informal bust portrait of her nephew, for which she was awarded a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship to study in Paris in 1929. There she studied briefly with Felix Benneteau at the Académie de la Grand Chaumière. She had two works accepted for the Salon d’Automne and exhibited at the Grand Palais in Paris. In 1931 Savage won a second Rosenwald fellowship, which permitted her to remain in Paris for an additional year. She also received a Carnegie Foundation grant for eight months of travel in France, Belgium, and Germany.

Following her return to New York in 1932, Savage established the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts and became an influential teacher in Harlem. In 1934 she became the first African American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors.

In 1937 Savage’s career took a pivotal turn. She was appointed the first director of the Harlem Community Art Centre and was commissioned by the New York World’s Fair of 1939 to create a sculpture symbolizing the musical contributions of African Americans.

Negro spirituals and hymns were the forms

Savage decided to symbolize in The

Harp. Inspired by the lyrics of James Weldon

Johnson’s poem Lift Every Voice and Sing, The Harp was Savage’s largest work and her last major commission. She took a leave of absence from her position at the Harlem Community Art Centre and spent almost two years completing the sixteen foot sculpture. Cast in plaster and finished to resemble black basalt, The Harp was exhibited in the court of the Contemporary Arts building where it received much acclaim. At the time, Savage was the only Black woman to be commissioned at the World’s Fair, and she was paid $360.

The sculpture depicted a group of twelve stylised Black singers in graduated heights that symbolised the strings of the harp. The sounding board was formed by the hand and arm of God, and a kneeling man holding music represented the foot pedal. No funds were available to cast The Harp, nor were there any facilities to store it. After the World’s Fair closed it was demolished, as was all the art.

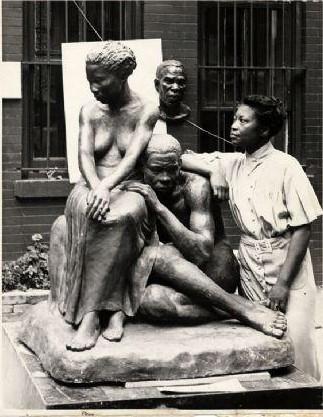

Augusta Savage at work on the sculpture, 1930s. https://timeline.com/augusta-savage-african-american-woman-sculptor-73c3d707fb33

Upon returning to the Harlem Community Art Centre, Savage discovered that her position had been assumed by someone else. This initiated a series of frustrations that virtually forced Savage to end her career. The Harlem Community Art Centre closed during World

War II, when federal funds were cut off. In 1939 Savage made an attempt to re-establish an art centre in Harlem with the opening of the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art. She was founder-director of the small gallery that was the first of its kind in Harlem. That venture closed shortly after its opening due to lack of money. During the spring of 1939, Savage held a small, one-woman show at the Argent Galleries in New York.

Despite the fact her own self-initiated art gallery only lasted a few months before it ran out of funding, she was keen on creating an infrastructure for Black artists, the need for a network for African American artists to succeed,” said Wendy Ikemoto, curator of a 2019 exhibition at the New York Historical Society “Savage once said in all the African American homes she visited, only two had artworks by African American artists. She asked:

How does the African American artist survive?’

She put a lot of thought and energy into creating these intellectual spaces and networks for the work of black artists.”

Depressed by the loss of her job and the collapse of both of her attempts to establish art centres, Savage retreated to the small town of Saugerties, New York, in the Catskill Mountains in 1945 and re-established relations with her daughter and her daughter’s family. Although her artistic production decreased, she found peace and seclusion in Saugerties. Savage visited New York occasionally, taught children in local summer camps, and produced a few portrait sculptures of tourists.

During her years in Saugerties, Savage also explored her interest in writing children’s stories, murder mysteries and vignettes, although none were published. In 1962 Savage moved back to New York and lived with her daughter. She died in relative obscurity on 26 March 1962, following a long bout with cancer.

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/augusta-savage-4269

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/may/08/augusta-savage-black-artist-newyork

Farris, Phoebe, ed. (1999). Women Artists of Colour : A bio-critical sourcebook to 20th century artists in the Americas. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313303746, pp. 272, 339–344.

Savage, Augusta (1988). “Augusta Savage and the art schools of Harlem”. Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture. New York Public Library. OCLC 645284036.

Etinde-Crompton, Charlotte, Crompton, Samuel Willard (2019) Augusta Savage: Sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance. ISBN 9781978505360

Daily Art Magazine: Augusta Savage: The Woman That Defined 20th Century Sculpture

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/may/08/augusta-savage-black-artist-newyork

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/30/us/augusta-savage-black-woman-artist-harlemrenaissance.html

https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/remembering-augusta-savage-only-black-womancommissioned-create-art-1939-worlds-fair https://sophia.smith.edu/afr111-f19/the-harp/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augusta_Savage#Individual_exhibitions