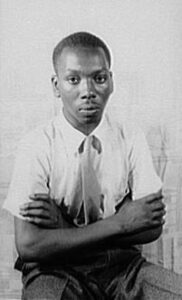

Thomas Joseph

1947

Commonwealth of Dominica

Dominica – British

Born in the Commonwealth of Dominica, Joseph came at the age of eight to London, where he still lives and works. In 1967 he studied at the Central School of Art and Design, following this with a BA course at the Slade School of Art, University of London.

He worked on Yellow Submarine, the 1968 animated film featuring the Beatles. He travelled in Europe and Asia during the 1970s, and subsequently enrolled at the London College of Printing, graduating with a Dip AD in Typographic design. While working for the magazine Africa Journal in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he also travelled extensively in Africa. In 1979 he illustrated Buchi Emecheta’s children’s book Titch the Cat, published by Allison and Busby.

According to InIVA (the Institute of International Visual Art) “Joseph’s work is often figurative and centered on the themes of reality, or rather the surreality of life in the city.”

In the documentary film Tam Joseph; Work in Progress he talks about his start as a painter and how he enjoys using tools he himself has made. This film was made over a period spanning seven years (2011–2017) and includes his work in sculpture, painting and graphic design.

He recognised Pablo Picasso as one of his main references in sculpture and admired how Picasso was capable of looking at things and offering a new interpretation of them.

One of Joseph’s best known paintings is his 1983 work Spirit of the Carnival,[2] a reference to the Notting Hill Carnival. Another notable work, dating from 1983, is UK School Report, which depicts the passage of a Black youth through the British education system in three portraits that are captioned: Good at sports, Likes music and Needs surveillance.

Countless images have been Tam Joseph’s constant companions since childhood. He has absorbed the work of Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Hokusai, Picasso, Matisse, and Soutine – painters who make difficult techniques look easy. It is always the ‘how’ more than the ‘what’ that places him in front of the same pictures, in the same museums. He says “Painting is about looking and interpreting and interpreting and looking again. It’s about scraping back to go forward.”

This last point is important, he explains. “Artists don’t have time to muck about. It is all about integrity and giving a hundred percent of your will before arriving at the hidden plateau.”

Of course, he says, a little money is good. Good quality artist’s materials have never come cheap, and he is quick to point out what he could do in a bigger studio – but he will not be held back.

Joseph was part of a collective exhibition based on migration in 2020. Around the world, border closures and national lockdowns have meant that the movement of people has largely ground to a halt. But for many refugees and asylum seekers, displaced by war, famine, and persecution, staying still is not an option. They are forced to make dangerous journeys until they are able to seek refuge in safer lands. In recent months we’ve seen some of these journeys captured in shocking detail on the news. The media has cast its collective eye on attempts to cross the Channel – usually on dangerously crowded dinghies – and has turned the act of migration into a politically charged discussion of rights.

What is thinking about migration without considering the borders that migrants have to pass through? Tam Joseph’s The Hand Made Map of the World (2013) reinterprets the navigational tool in an act of radical boundary-blurring and urges us to consider the harmful geopolitics of borders.

‘People cross borders. / It’s been that way ever since / borders crossed people,’ writes Antoine Cassar in his 8 no-border haiku, and as we explore the new narratives that can emerge from Joseph’s exercise of border-swapping, we realise that much of the histories of these perimeters are rooted in dispute and war.

These works mark different points in each individual’s complex journey of separation, waiting, and longing. Whether depicting a scene of tragedy or as an expression of personal anguish, beneath the exterior of migration themed art often lies an urgent call to action. These works resonate with this moment of crisis, and urge us to act.

Tam Joseph has exhibited widely including in Newly Orion, The Sterling Smith Gallery, The Whitechapel Art Gallery, The Gallery HD Nick in Aubais, The Gallerie Salamandre in France, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, The ICA, The Perez Museum of Art and the Queens Museum of Art in the United States. His paintings have travelled throughout the UK and America. The internet gives access to The Spirit of the Carnival (1982), School Report (1980) and The Flying Doctor (1994).

Image source https://www.felixandspear.com/tam-joseph

https://www.felixandspear.com/tam-joseph

https://www.nocolourbar.org/tam-joseph

https://artuk.org/discover/stories/tam-joseph-talks-to-catherine-farren

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tam_Joseph#cite_note-4

https://www.tamjosephartlive.com