Alma Woodsey Thomas

Alma Thomas (1891-1978) was a pioneering abstract artist who dared make her way in a white, maledominated abstract art world. She was the first African American woman to receive a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The year was 1972, and Alma Thomas was 80 years old.

1891

1978

Georgia, U.S.

African – American

Watercolours by Alma Thomas, 1960, Dupont Theatre Art Gallery

Alma Thomas: A Retrospective Exhibition (1959-1966), 1966, Howard University Gallery of Art

Alma Thomas: Recent Paintings, 1968, Franz Bader Gallery

Recent Paintings by Alma W Thomas: Earth and Space Series (1961–1971), 1971, Carl Van Vechten Gallery, Fisk University

Alma W. Thomas, 1972, Whitney Museum of American Art

Alma W. Thomas: Retrospective Exhibition, 1972, Corcoran Gallery of Art

Alma W. Thomas: Paintings, 1973, Martha Jackson Gallery

Alma W. Thomas: Recent Paintings, 1975, Howard University Gallery of Art

Alma W. Thomas: Recent Paintings, 1976, H.C. Taylor Art Gallery, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University

A Life in Art: Alma Thomas, 1891-1978, 1981, National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Alma W. Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintings, 1998, Fort Wayne Museum of Art, Tampa Museum of Art, New Jersey State Museum, Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, and The Columbus Museum

Alma Thomas: Phantasmagoria, Major Paintings from the 1970s, 2001, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, and Women’s Museum: An Institution for the Future

A Proud Continuum: Eight Decades of Art at Howard University, 2005, Howard University

Colour Balance: Paintings by Felrath Hines and Alma Thomas, 2010, Nasher Museum of Art

Alma Thomas, 2016, The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College,[66] and The Studio Museum in Harlem

Alma Thomas: Resurrection Exhibition, 2019, Mnuchin Gallery

Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful, 2021, Chrysler Museum of Art

Alma Thomas was born on 22 September 1891 in Columbus, Georgia. She was the oldest of the four daughters of to John Harris Thomas, a businessman, and Amelia Cantey Thomas, a dress designer. Her mother and aunts, she later wrote, were teachers and Tuskeegee Institute graduates. She was creative as a child, although her serious artistic career began much later in life. While growing up, Thomas displayed her artistic capabilities, and enjoyed making small pieces of artwork such as puppets, sculptures, and plates, mainly out of clay from the river behind her childhood home. Despite a growing interest in the arts, Thomas was not allowed to go into art museums as a child. She was provided with music lessons, as her mother played the violin.

In 1907, when Thomas was 16, the family moved to the Logan Circle neighborhood of Washington DC to escape racial violence in Georgia and to seek the benefits of the public school system of Washington. Her parents made this move despite that the family descended the social scale in leaving their uppermiddle class life in

Georgia.

Describing the reason for the family move she later wrote “When I finished grade school in Columbus, there was nowhere that I could continue my education, so my parents decided to move the family to Washington.” Other writers have pointed to the Atlanta race riots and racial massacre of 1906 as among the reasons her family left Georgia. As another example of the racial violence that her family faced in Georgia, Alma’s father had an encounter with a lynch mob shortly before Alma was born, and her family attributed her poor hearing to the fright from that incident. Although still segregated, the nation’s capital was known to offer more opportunities for African Americans than most other cities. As she wrote in the 1970s, “At least Washington’s libraries were open to Negroes, whereas Columbus excluded Negroes from its only library.”

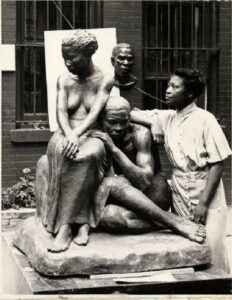

Thomas entered Howard University in 1921 when she was aged 30, entering as a junior because of her previous teacher training. She started as a home economics student, planning to specialize in costume design, only to switch to fine art after studying under art department founder James V Herring. Her artistic focus at Howard was on sculpture; the paintings she produced during her college education were described by Romare Bearden and Henry Henderson as academic and undistinguished. She earned her Bachelors of Science in Fine Arts in 1924 from Howard, becoming the first graduate from the University’s Fine Arts programme, and also possibly the first AfricanAmerican woman to earn a Bachelor’s degree in art. —She may well have been the first American woman of any racial background to achieve this. The artist Keith Anthony Morrison wrote that “it was said [in 1924] that she was the first woman in America ever to gain a bachelor’s degree in art.”

Thomas would not become a full time, professional artist until she was 68 years old, in 1960, when she retired from teaching.

Twelve years after her first class at American, she began creating Colour Field paintings, inspired by the work of the New York School and Abstract Expressionism.

Thomas was known to work in her home studio, which wasa small living room, creating her paintings by propping the canvas on her lap and balancing it against the sofa. She worked out of the kitchen in her house, creating works like Watusi (Hard Edge) (1963), a manipulation of

the Matisse cutout The Snail, in which Thomas shifted shapes around and changed the colours that Matisse used, and named it after a Chubby Checker song.

In contrast with most other members of the Washington Colour School, she did not use masking tape to outline the shapes in her paintings. Her technique involved drawing faint pencil lines across the canvas to create shapes and patterns and filling in the canvas with paint afterwards. Her pencil lines are obvious in many of her finished pieces, as Thomas did not erase them.

Thomas’s post-retirement artwork had a notable focus on colour theory. Her work at the time resonated with that of Wassily Kandinsky (who was interested in the emotional capabilities of colour) and of the Washington Colour Field Painters, “something that endeared her to critics, but also raised questions about her ‘blackness’ at a time when younger AfricanAmerican artists were producing works of racial protest.” She stated, “The use of colour in my paintings is of paramount importance to me. Through colour I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness in my painting rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” Speaking again about her use of colour she said: “Colour is life, and light is the mother of colour.”

In 1963, she walked in the March on Washington with her friend, the opera singer Lillian Evans. Although Thomas was largely an apolitical artist, she portrayed the 1963 event in a 1964 painting. A detail from that painting became a 2005 U.S. postage stamp commemorating the March on Washington.

Her first retrospective exhibit was in 1966 (April 24–May 17) at the Gallery of Art at Howard University, curated by art historian James A. Porter. It included 34 works from 1959 to 1966. For this exhibition, she created Earth Paintings, a series of nature-inspired abstract works, including Resurrection (1966), which in 2014 would be bought for the White House collection. Thomas and the artist Delilah Pierce, a friend, would drive into the countryside where Thomas would seek inspiration, pulling ideas from the effects of light and atmosphere on rural environments.

To meet the challenge posed by the Howard show, according to Romare Bearden and Henry Henderson, her style changed again, in a crucial way: “Thomas evolved the specific style now recognized as her signature – playing colour against colour and over colour with small, irregular rectangular shapes of dense, often intense colour.” This exhibition received a supportive review from Helen Hoffman in The Washington Post of May 4, 1966, titled Colourful abstract reflects her spirit.

Inspired by the moon landing in 1969, Alma Thomas began her second major theme of paintings. The series Space, Snoopy and Earth were applying pointillism. She evoked mood by dramatic contrast of colour with mosaic style, using dark blue against pale pink and orange colours, depicting an abstraction and accidental beauty through the use of colour. Most of the works in these series have circular, horizontal and vertical patterns. These patterns are able to generate a conceptual feeling of floating. The patterns also generate energy within the canvas. The contrast of colours creates a powerful colour segregation and maintain visual energy.

In 1972, at the age of 81, Thomas was the first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and later the same year a much larger exhibition was also held at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Thomas denied labels placed upon her as an artist and would not accept any barriers inhibiting her creative process and art career, including her identity as a Black woman. She believed that the most important thing was for her to continue to create her visions through her own artwork and work in the art world despite racial segregation. Despite this, Thomas was still discriminated against as a Black female artist and was critiqued for her abstract style as opposed to other Black Americans who worked with figuration and symbolism to fight oppression. Her works were featured alongside many other African American artists in galleries and shows, such as the first Black owned gallery in the District of Columbia.

After her show at the Whitney, Thomas’s fame within the fine arts community immediately skyrocketed. Her newfound recognition was due in part to Robert Doty’s vocal support of her, as he organized Thomas’s Whitney show as part of a series of African American artist exhibitions, intended to protest their lack of representation. New York critics were impressed with Thomas’s modern style, especially given the fact that she was a nearly 80yearsold woman at the time of her national debut. The New York Times reviewed her exhibit four times, calling her paintings “expert abstractions, tachiste in style, faultless in their handling of colour .” Many white critics complimented her as `the Signac of current colour painters’ and as `gifted, ebullient

abstractionist’. Alma Thomas’s philosophy of her own art is that her works are full of energy, and those energies cannot be destroyed or created.

Thomas was, according to all evidence, never married. She told the New York Times in 1977 that she had “never married a man but my art. What man would have ever appreciated what I was up to?”

Thomas lived in the same family house in Washington, at 1530 15th Street, for almost her entire life, from 1907 until her death in 1978. Her younger sister John Maurice Thomas, who was named for their father and had a career as a librarian at Howard University, shared the house with her.

Alma Thomas died on 24 February 1978, in Howard University Hospital, following aortal surgery.

https://www.culturetype.com/2019/07/16/50-years-ago-alma-thomas-made-space-paintings-that-imagined-the-moon-and-mars/

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/alma-thomas-4778

https://www.wikiart.org/en/alma-woodsey-thomas