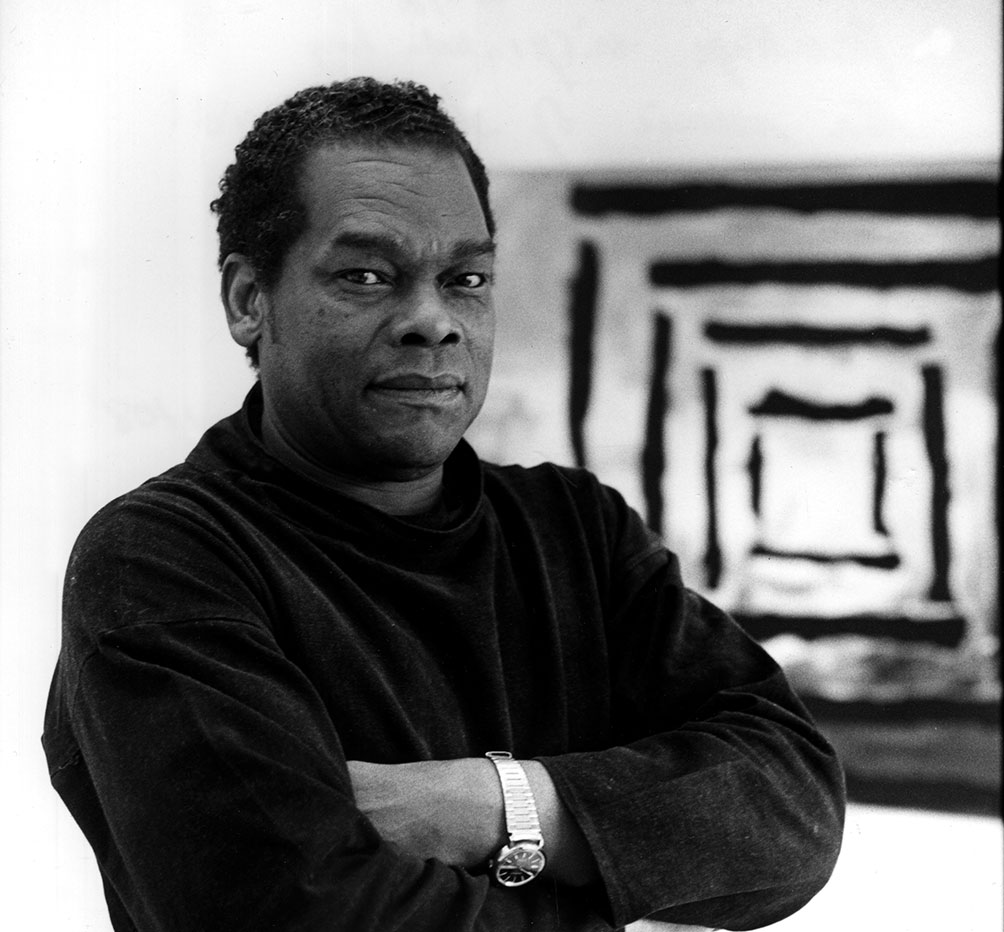

Aubrey Williams (1926 Guyana – 1990 London), is a key figure of PostWar painting in Britain. He was a founding member of the 1960s Caribbean Artists Movement, received the Commonwealth Prize in Painting from Queen Elizabeth II in 1965, and the Golden Arrow of Achievement from the Guyanese government in 1979.

1926

1990

Georgetown, British Guiana

Guyanese

Born in Georgetown in British Guiana (now Guyana), Williams began drawing and painting at an early age. He received informal art tutoring from the age of three, and joined the Working Peoples’ Art Class at the age of 12. After training as an agronomist he worked as an Agricultural Field Officer for eight years, initially on the sugar plantations of the East Coast and later in the North West region of the country, an area inhabited primarily by the indigenous Warao people. His time among the Warao had a dramatic impact on his artistic approach, and initiated the complex obsession with pre-Columbian arts and cultures that ran throughout his artistic career.

He spent time in Italy, France and Germany. Williams arrived in England in 1952 at the age of 26. He took up accommodation at Hans Crescent in London – an area that was, according to him, populated by the “colonial elite, the sons of Maharajas, the upper middle classes”. He later described Hans Crescent as part of “British brainwashing and indoctrination” because “after living like [that] for a few months you would begin to despise your own people back home”,

He enrolled on a course in Agricultural Engineering at the University of Leicester, but following discouragement from his university lecturers and growing feelings of discomfort with his accommodation, he dropped his University course and embarked on a period of travel in Europe and the UK. During his travels he met Albert Camus whointroduced him to Pablo Picasso. For Williams, the meeting with Picasso was a `big disappointment’ when the Spanish painter told him that he had a very fine African head and said that he would like Williams to pose for him. “I felt terrible,” Williams recalled. “In spite of the fact that I was introduced to him as an artist, he did not think of me as another artist. He thought of me only as something he could use for his own work”.

On returning from his travels in 1954, Williams enrolled as a student at St Martin’s School of Art. He studied at St. Martin’s for more than two and a half years. In his second year, however, he decided that he wanted to use the school’s facilities and resources but did not want their diploma and thus did not register after this time. In 1954 he held his first exhibition at the little-known Archer Gallery in Westbourne Grove in London. During these early years in London, Williams married his partner, Eve Lafargue, who had travelled with him from British Guiana.

While Williams maintained a base in London until the end of his life, from 1970 onwards he spent large amounts of time working overseas in Jamaica, Florida and, less frequently, Guyana. In February 1970 he travelled to Guyana with a group of Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) artists – including Brathwaite, Harris, Salkey and Sam Selvon – for a Caribbean Writers and Artists Convention that was organised by the Guyanese government as part of the 1970 Guyana Republic Celebrations, This was the first time he had returned to Guyana since 1952, and he received the national honour of The Golden Arrow of Achievement. In the same year he completed a government commissioned series of five murals, named Timehri, at the Cheddi Jagan International Airport. 1970 was also the year in which Williams first travelled to Jamaica, after which he spent several months in Jamaica every year and was ultimately appointed Artist in Residence at the Olympia Art Centre in Kingston.

In 1972 he took part in the first Carifesta in Guyana, which ran from 25 August to 15 September.

In 1976 he completed two murals in Jamaica, at the School of Hope for Mentally Handicapped Children, and at the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Swallowfield Road.

In 1977 he exhibited work as a participant in the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (Festac ’77) held in Lagos, Nigeria, from 15 January to 12 February, together with other UKbased Black artists, including Winston Branch, Ronald Moody, Uzo Egonu, Armet Francis, Emmanuel Taiwo Jegede and Donald Locke.

In May 1978 he completed a mural in Howe Hall at the University of Dalhousie, which was commissioned by Forbes Burnham, Prime Minister of Guyana at that time. .

In the 1980s Williams worked mainly in a studio in Florida. During these years he produced three of his bestknown series of paintings: Shostakovich, The Olmec-Maya and Now and Cosmos. His Shostakovich exhibition at London’s Commonwealth Institute in 1981 received scant coverage in the national press, but art critic Guy Brett wrote in Index on Censorship that “Aubrey Williams is able, to paint with epic power on a large scale. His paintings are a rare thing — a remarkable homage of one artist to another, and also of one medium to another. I felt his exhibition was a tonic to the whole art scene here, regardless of where one places oneself in the movement of styles and ideas. Yet it passes with virtually no comment in the cultural press. …Yet he has lived and worked in Britain since 1954! It begins to be clear what Williams means when he describes himself as an ‘exile’ in this country, and how his situation is linked with the way the cultural establishment here boycotts artists who don’t fit in with a traditional image of British art.”

In 1986 the Guyanese government awarded him The Cacique’s Crown of Honour, and that year he was the subject of a documentary film directed by Imruh Caesar entitled The Mark of the Hand, which was first screened at the British Academy of Film and Television Arts in London on 16 December 1986.

In 1989 paintings by Williams were included in an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery entitled The Other Story, which focused on the work of African and Asian artists in post-World War II Britain. This was the first time that his work was exhibited in a mainstream public art gallery in the UK, and featured his Cosmos series. In the words of Geoffrey MacLean “It showed the vast span of Williams’s spiritual and intellectual development, from the birds of Guyana and the environment of his childhood, through the memory of his Amerindian heritage, culminating in an appreciation of universal expression Williams has been exhibited in a wide range of contexts and institutions, including Rasheed Araeen’s The Other Story (1989), the Whitechapel Art Gallery’s major retrospective, and a room display at Tate Britain. In 2010, October Gallery linked with the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool to produce two simultaneous Aubrey Williams exhibitions. In 2014, a symposium on his work was held at Cambridge University with another at October Gallery in 2015, highlighting the fact that his works still resist classification while attracting ever more attention.

Williams’ recent exhibitions include: The Gift of Art (2018) at the Perez Museum, Get Up, Stand Up Now (2019) at Somerset House, Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 50s – Now (2021) at Tate Britain, Post-War Modern New Art in Britain 1945–1965 (2022) at the Barbican, Fragments of Epic Memory (2021) at the Art Gallery of Ontario and Afro Scots: Revisiting the Work of Black Artists in Scotland (2022) at Glasgow Museums.

The Caribbean Artists Movement[

In the mid-1960s Williams joined forces with a small group of Londonbased Caribbean intellectuals and artists to found the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM). The other founding members of the movement were Kamau Brathwaite, Wilson Harris, Louis James, Evan Jones, John La Rose, Ronald Moody, Orlando Patterson and Andrew Salkey. Active for six years (from 1966 to 1972), CAM took the form of meetings, readings, exhibitions, seminars and conferences, which sought to provide a forum for Caribbean artists to exchange ideas, address particular artistic issues, and discuss each other’s work. It began as a series of small, private meetings held in members’ homes but quickly expanded into larger, public events.

Williams was a regular at CAM events and played an important pioneering role in the movement, which was to have an inestimable influence on the British art scene for the next fifteen years. In April 1967 he held an informal meeting at his studio in which he talked about his work, his creative process, his influences and philosophy. The meeting was attended by Brathwaite, La Rose, Salkey and Harris.[37] At CAM’s first Symposium of West Indian Artists, which was held at the West Indian Students’ Centre in Earl’s Court on 2 June 1967, Williams gave a short speech about themes in Caribbean art. He also attended the first CAM conference in September 1967 at the University of Kent, and presented a paper entitled The Predicament of the Artist in the Caribbean. In this paper he argued against ideas that art should be figurative or narrative, while also suggesting that Caribbean artists need not turn to contemporary European artists for examples of more abstract or non-narrative forms; they could, instead, find precedents in the `primitive’ art of South America and the Caribbean. In May 1960 he contributed a number of paintings to CAM’s first art exhibition.

Williams described CAM as very important both for himself and for other Caribbean artists. “It helped create an intellectual atmosphere for everyone to be creative and relate to each other”, he said, and provided an international platform through which individual members came to know what was happening in the rest of the Commonwealth and through which he personally met other artists from Africa, from India and from many parts of the world.

https://octobergallery.co.uk/artists/williams

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/aubrey-williams-2314

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aubrey_Williams