Beryl Agatha Gilroy (née Answick)

A teacher, novelist, an ethno-psychotherapist, and poet who has been described as one of Britain’s most significant post-war Caribbean migrants’ part of the Windrush generation.

30 August 1924

4 April 2001

British Guiana

Guyanese

1945 – graduated teacher training college in Georgetown, gaining a firstclass diploma.

First teaching job

1951 – at the age of 27, she was selected to attend university in the United Kingdom

1953 – she attended the University of London, pursuing a Diploma in Child Development. 1953-56 – taught in Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) schools

1954 – marriage to Patrick Gilroy

1956 – first child, Paul Gilroy is born

1968 – Gilroy was appointed as a deputy head teacher

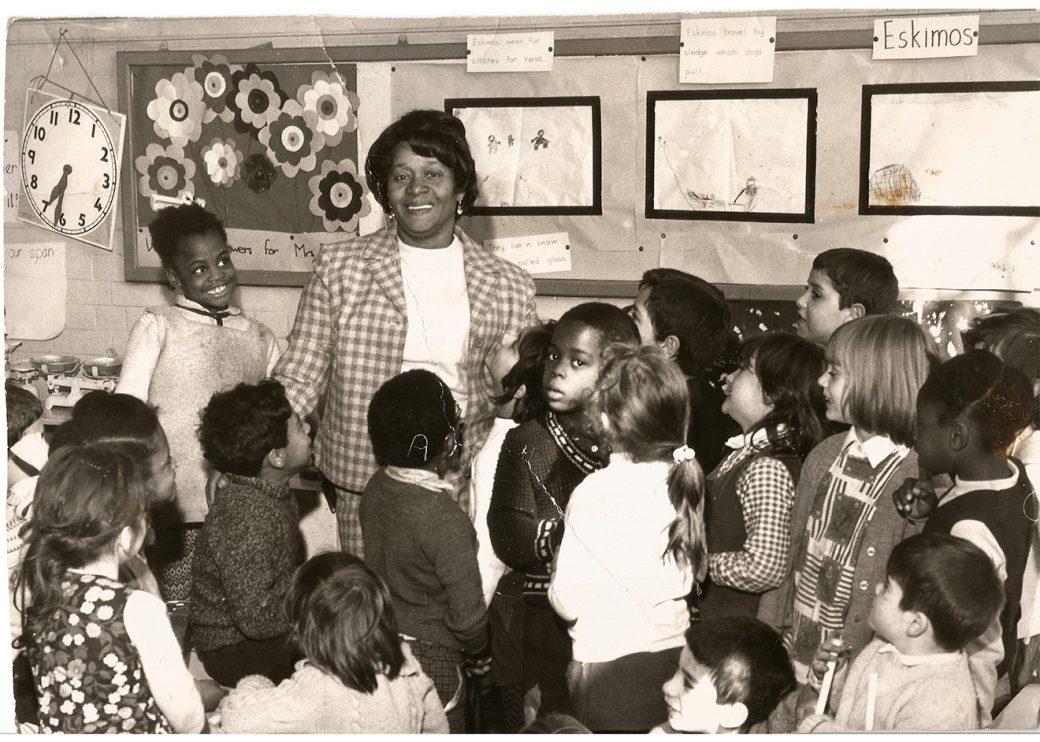

1969 – became the first Black woman headteacher in the London borough of Camden

1975 – Husband dies

1976 – Autobiographical book Black Teacher published

1982 – Gilroy joined London University’s Institute of Education and the ILEA’s Centre for Multicultural Education.

1986 – Gilroy’s first novel, the award-winning Frangipani House was published

1987 – gained a PhD in counselling psychology from an American university

1989 – Boy Sandwich was published

1990 – honoured by the Greater London Council for all of her services in education

1991 – Stedman and Joanna: A Love in Bondage

1991 – collection of poems, Echoes and Voices published

1994 – Sunlight and Sweet Water, Gather the Faces, In Praise of Love and Children and Inkle and Yarico published

1995 – Gilroy received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of North London.

1996 – Gilroy was honoured by the Association of Caribbean Women Writers and Scholars

2000 – Gilroy was made an Honorary Fellow

2001 – The Green Grass Tango novel was posthumously published

Beryl Gilroy was born in Skeldon, Berbice, Guyana. She grew up in a large, extended family, largely under the influence of her maternal grandmother, Sally Louisa James (1868–1967), a herbalist, who managed the family smallholding, was a keen reader and imparted to the young Beryl stories of Long Bubbies, Cabresses and Long Lady and a treasury of colloquial Guyanese proverbs. She was raised by her maternal grandmother from the age of two, following a period of illness.

Gilroy did not enter fulltime schooling until she was 12; this was influenced by her grandmother, Sally Louisa James, who thought Gilroy would be able to learn more if she had different life experiences and more freedom, not something typically gained from primary school. Gilroy was heavily influenced by her grandmother in all her aspects of life, and she found inspiration from her grandmother’s stories in her own writings.

From 1943 to 1945, she attended teacher training college in Georgetown, gaining a first class diploma. She subsequently taught and lectured on a UNICEF nutrition programme. In 1951, at the age of 27, she was selected to attend university in the United Kingdom. Between 1951 and 1953 she attended the University of London, pursuing a Diploma in Child Development.

Gilroy’s first teaching job was in Guiana from the late 1940s until 1951. She subsequently left Guiana and attended the University of London. Gilroy assumed that since she was a qualified and respected teacher from Guiana, she would not have a problem looking for a teaching job in London. However, during this time, racism was still strongly prevalent. Her prospective employers denied her work for a long time because she was a Black woman. She was employed by the Inner London Education Authority, at a `poor Catholic school’. She taught for a couple of years, married scientist Patrick Gilroy (d 1975), and spent the next 12 years at home bringing up and educating their children Darla and Paul, furthering her own higher education. In 1968 she returned to teaching and eventually became the first Black headteacher in London at Beckford School in West Hampstead. It was difficult for her during this time, since many of her co-workers were prejudiced against her, and she received a low wage compared to other teachers at her school. However, she continued teaching regardless of these factors. Many of the experiences she had as a teacher in London led her to write her novel Black Teacher (1976).

Black Teacher (1976)

Black Teacher was written to not only show the experience of a woman teacher but as a Black woman teacher. It was widely received as disturbing information rather than being seen as a narrative. One reviewer wrote that `The heroine of Black Teacher is at times boastful, defensive, aggressive, kind and humorous. She is a flawed human being in the process of finding her place in an alien society that failed to appreciate her and where racial abuse was rife. Reflecting this instability, the narrator’s voice slips between a third-person ‘pedantic’ narrator who is confident, professional and self-assured and the autobiographical ‘I’ which is much more provisional and self-doubting. Gilroy moves the narrator between the multiple identities that she has created to deal with difficult situations.’

This book was meant to showcase Gilroy’s personal experiences teaching in London. Most of the reviewers were other teachers, who claimed that her experiences were not the ones she had written about in Black Teacher. They tried to discredit it, by claiming it was easier than she had described to get a job as a teacher, and that the racism in the book was not likely to be as bad as she perceived it to be.

The book was republished by Faber in July 2021, meeting with positive reviews in The Guardian and the London Review of Books.

Gilroy had many other jobs besides teaching. She worked in a café, she was a maid, a dishwasher, and a worked in a factory. While she was homeschooling her children she would also read and review works for a publisher.

Later, she worked as a multicultural researcher at the Institute of Education, University of London, and developed a pioneering practice in psychotherapy, working mainly with Black women and children. She was a co-founder, in the early 1980s, of the Camden Black Sisters group. Gilroy gained a PhD in counselling psychology from an American university in 1987 whilst working at the Institute of Education.

Her 1976 memoir about her experiences as the first Black headteacher in London is described by Sandra Courtman as `an unconventional autobiography … [Black Teacher] is Gilroy’s experiment with an intermediary form – somewhere between fiction and autobiography, with a distinct non-linear structure.’ It was not until 1986 that Gilroy’s first novel, the award winning Frangipani House was published (Heinemann). It won a GLC Creative Writing Prize in 1982. Set in an old person’s home in Guyana, it reflects one of her professional concerns: the position of ethnic minority elders and her persistent emphasis on the drive for human freedom. Boy Sandwich (Heinemann) was published in 1989, followed by Stedman and Joanna: A Love in Bondage (Vantage, 1991), and a collection of poems, Echoes and Voices (Vantage, 1991). Then came Sunlight and Sweet Water, Gather the Faces, In Praise of Love and Children and Inkle and Yarico (all Peepal Tree, 1994). Her last novel, The Green Grass Tango (Peepal Tree) was posthumously published in 2001, after Gilroy’s death in April of that year.

Gilroy’s early work examined the impact of life in Britain on West Indian families and her later work explored issues of African and Caribbean diaspora and slavery.

In 1998, a collection of her non-fiction writing, entitled Leaves in the Wind, came out from Mango Publishing. It included her lectures, notes, essays, dissertations, and personal reviews. In this book she stated that the purpose behind Black Teacher and much of her other writing was “to set the record straight. There had been Ted Braithwaite’s To Sir With Love [1959] and Don Hinds’ Journey to an Illusion [1966] but the woman’s experiences had never been stated.” She also later noted: “In the tradition of Black women who write to come to terms with their trauma, or alternatively to understand the nature of their elemental oppression, I wrote to redefine myself and put the record straight.”

In Gilroy’s writings she drew much of her inspiration from stories her grandmother would tell her about British Guiana. She also was inspired from her own life experiences, such as her work before becoming a teacher, and the racism she experienced whilst being one of the first Black head teachers in London.

Although many of Gilroy’s peers who were writing Caribbean Literature were being published, Gilroy was often turned away in the beginning. Her writings were seen to be too `…colonial, and unknowing, and … psychological and strange.’ Some of her writings were not published for more than 30 years after she had written them. After many years, she was finally able to share her work with the public, and to this day she is remembered as a part of the Black feminist movement. However, that is not the way in which she wanted to be remembered. `She badly wanted to avoid being marginalised by any literary or Black-feminist political label.’

Writing style

Beryl Gilroy was a Caribbean fiction and nonfiction writer. Many of her writings at the beginning of her career were postcolonial fiction novels and short stories. Towards the end of her career she published a collection of her journals, lecture notes, essays and personal reviews. Her fiction writings were inspired by her life, and stories she was told by her grandmother in her childhood in Guiana. Her writings typically were based on Caribbean characters, many of which are women Caribbean characters. It has been said that she wrote from the woman’s perspective because that is what she knew. Gilroy wanted to give Black women something they could relate to. At the time, many of the other Caribbean writers that were published were writing from the male point of view. As Courtman notes “Writing at the ‘wrong’ time and in the ‘wrong’ gender, the work of Beryl Gilroy was subject to misunderstandings and neglect. But Gilroy was the ultimate outsider who broke down barriers to clear a cultural and creative space for subsequent generations.”

After many years of neglect in Beryl Gilroy’s life she finally began receiving recognition for her work. She eventually received many honours, and awards late in her career as a writer. Gilroy wrote The Nippers Series which was written throughout the 1960s-1970s, they were several short stories made for children. This series won her over sixteen awards. She received the GLC Creative Writing Prize for her novel Frangipani House from 1986. Gilroy was honoured in 1990 by the Greater London Council for all of her services in education. Five years later, in 1995, Gilroy received an Honorary Doctorate from the University of North London. In 1996, Gilroy was honoured by the Association of Caribbean Women Writers and Scholars. Then in 2000, Gilroy was made an Honorary Fellow, a highly prestigious award that a University can give from the Institute of Education.

In recognition of Beryl Gilroy, an orange skirt suit she wore was included in an exhibition titled Black British Style at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2004.

She also received a British Guiana Teacher’s Certificate with firstclass honours in the 1950s

She married Patrick Gilroy, and her children were the academic Paul Gilroy, and Darla Gilroy. Gilroy was heavily influenced by her grandmother in all her aspects of life, and she found inspiration from her grandmother’s stories in her own writings. She also used the same methodology that her grandmother used when it came to schooling her own children. Gilroy homeschooled her son and daughter with the same focus on freedom that her grandmother had for her.

Links to wider Resources:

Black Teacher by Beryl Gilroy review – bigotry in the classroom | Autobiography and memoir | The Guardian

Beryl Gilroy | Peepal Tree Press

VIRTUAL: Black Teacher by Beryl Gilroy with Darla Gilroy | Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) – UCL – University College London

Paul Gilroy – Wikipedia

Credits

Beryl Gilroy – The British Library (bl.uk)

Beryl Gilroy – Wikipedia

Beryl Gilroy | Books | The Guardian

Marina Warner · I ain’t afeared: In Her Classroom · LRB 9 September 2021