Mary Edmonia Lewis

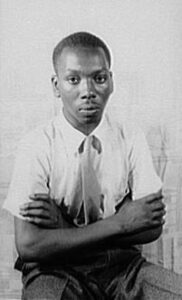

Mary Edmonia Lewis, Wildfire (c. 4 July 1844 – 17 September 1907) was an American sculptor of mixed African American and Native American (Mississauga Ojibwe) heritage. Born free in Upstate New York, she worked for most of her career in Rome, Italy. She was the first African American and Native American sculptor to achieve national and then international prominence. She began to be recognised in the United States during the Civil War and by the end of the 19th century was the only Black woman artist who had been recognized to any extent by the American artistic mainstream. In 2002 the scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Edmonia Lewis on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

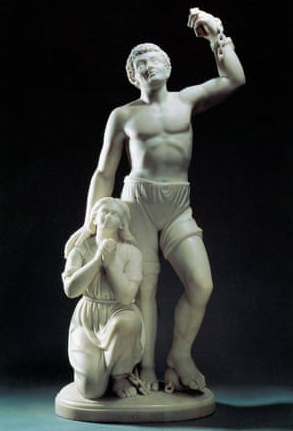

Her work is known for incorporating themes relating to Black people and indigenous peoples of the Americas into neoclassical style sculpture.

1844

1907

Upstate New York

African – American

Art of the American Negro Exhibition, American Negro Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, 1940

Howard University, Washington DC, 1967

Vassar College, New York, 1972

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, 200.

Edmonia Lewis and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: Images and Identities at the Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 18 February–3 May 1995

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC, 7 June 1996 – 14 April 1997

Wildfire Test Pit, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, August 30, 2016 – June 12, 2017.

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, (2019), Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States. • Edmonia Lewis’ Bust of Christ, Mount Stuart, UK

According to the American National Biography, reliable information about her early life is limited, and it says that Lewis “was often inconsistent in interviews even with basic facts about her origins, preferring to present herself as the exotic product of a childhood spent roaming the forests with her mother’s people.” On official documents she gave 1842, 1844, and even 1854 as her birth year.

Edmonia

Lewis was born about 4 July 1844 in the former town of Greenbush, Rensselaer County, New York. Her mother, Catherine Mike Lewis was an excellent weaver and craftswoman and was of American Indian( Mississauga Ojibwe) and African American descent.Her father was African American, but his identity is not confirmed. By the time Lewis reached the age of nine, both of her parents had died and she and her half brother were adopted by two maternal aunts and lived with themnear Niagara Falls, New York.

Lewis and her aunts sold Ojibwe baskets and other items to tourists visiting Niagara Falls, Toronto, and Buffalo. During this time, Lewis went by her Native American name, Wildfire, while her brother was called Sunshine. In 1852, her brother left for, California.

Samuel Lewis made a fortune in the California gold rush and subsequently took care of his sister, supplying her with `her every want anticipating her wishes after the style and manner of a person of ample income’.

In 1856, Mary Lewis enrolled in a pre-college programme at New York Central College, a Baptist abolitionist school where she met many of the leading activists who would become her mentors, patrons, and subjects for her work. In a later interview, Lewis said that she left the school after three years, having been “declared to be wild.”

However, her academic record shows that her grades, conduct, and attendance were all exemplary. Her classes included Latin, French, grammar, arithmetic, drawing, composition, and declamation (public speaking).

Education

In 1859, when Edmonia Lewis was 15 years old she attended the Oberlin Academy Preparatory School for three years before entering Oberlin Collegiate Institute (since 1866, Oberlin College). This was one of the first higher learning institutions in the United States to admit women and people of differing ethnicities. The Ladies’ Department was designed `to give Young Ladies facilities for the thorough mental discipline, and the special training which will qualify them for teaching and other duties of their sphere.’ She changed her name to Mary Edmonia Lewis and began to study art. Lewis boarded with Reverend John Keep and his wife from 1859 until she was forced from the college in 1863. At Oberlin, with a student population of one thousand, Lewis was one of only thirty students of colour. Reverend Keep was white, a member of the board of trustees, an avid abolitionist, and a spokesperson for coeducation.

Mary said later that she was subject to daily racism and discrimination. She, and other female students, were rarely given the opportunity to participate in the classroom or speak at public meetings.

During the winter of 1862, several months after the start of the Civil War, an incident occurred between Lewis and two Oberlin classmates, Maria Miles and Christina Ennes. The three women, all boarding in Keep’s home, planned to go sleigh riding with some young men later that day. Before the sleighing, Lewis served her friends a drink of spiced wine. Shortly after, Miles and Ennes fell severely ill. Doctors examined them and concluded that the two women had some sort of poison in their system, supposedly cantharides, a reputed aphrodisiac. For some time it was not certain that they would survive. Days later, it became apparent that the two women would recover from the incident. Authorities initially took no action.

News of the controversial incident rapidly spread throughout Ohio. In the town of Oberlin, where the general population was not as progressive as at the college, while Lewis was walking home alone one night she was dragged into an open field by unknown assailants, badly beaten, and left for dead. After the attack local authorities arrested Lewis, charging her with poisoning her friends. John Mercer Langston, an Oberlin College alumnus and the first African American lawyer in Ohio, represented Lewis during her trial. Although most witnesses spoke against her and she did not testify, Chapman moved successfully to have the charges dismissed: the contents of the victims’ stomachs had not been analysed and there was, therefore, no evidence of poisoning. The remainder of Lewis’ time at Oberlin was marked by isolation and prejudice. About a year after the poisoning trial, Lewis was accused of stealing artists’ materials from the college. She was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Only a few months later she was charged with aiding and abetting a burglary. At this point she had had enough and left. Another report says that she was forbidden from registering for her last term, leaving her unable to graduate.

Lewis moved to Boston in early 1864, where she began to pursue her career as a sculptor. She repeatedly told a story about encountering in Boston a statue of Benjamin Franklin, not knowing what it was or what to call it but concluding she could make a `stone man’herself.

The Keeps wrote a letter of introduction on Lewis’ behalf to the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison in Boston, as did Henry Highland Garnet. He introduced her to already established sculptors in the area, as well as writers who publicised Lewis in the abolitionist press. Finding an instructor, however, was not easy for her. Three male sculptors refused to instruct her before she was introduced to Edward Augustus Brackett (1818–1908), who specialised in marble portrait busts. His clients were some of the most important abolitionists of the day, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, and John Brown.

He lent her fragments of sculptures to copy in clay, which he critiqued. Under his tutelage she crafted her own sculpting tools and sold her first piece, a sculpture of a woman’s hand, for $8. Anne Whitney, a fellow sculptor and friend of Lewis’, wrote in an 1864 letter to her sister that Lewis’s relationship with her instructor did not end amicably, but did not disclose the reason for the split. Lewis opened her studio to the public in her first solo exhibition in 1864.

Lewis was inspired by the lives of abolitionists and Civil War heroes. Her subjects in 1863 and

1864 included some of the most famous abolitionists of her day: John Brown and Colonel Robert

Gould Shaw. When she met Colonel Shaw, the commander of an African American Civil War regiment from Massachusetts she was inspired to create a bust of his likeness, which impressed the Shaw family, who purchased it. Lewis then made plaster cast reproductions of the bust and sold one hundred at 15 dollars apiece. This was her most famous work to date and the money she earned allowed her to move to Rome. Anna Quincy Waterston, a poet, wrote a poem about both Lewis and Shaw.

From 1864 to 1871, Lewis was written about or interviewed by Lydia Maria Child, Elizabeth

Peabody, Anna Quincy Waterston, and Laura Curtis Bullard, who were all important women in Boston and New York abolitionist circles. Articles about Lewis appeared in important abolitionist journals, including Broken Fetter, the Christian Register, and the Independent, as well as many others. Lewis was not opposed to the coverage she received in the abolitionist press, and she did not turn down monetary aid, but she could not tolerate false praise. She felt that some people did not really appreciate her art but saw her as an opportunity to express and show their support for human rights.

Rome

Minnehaha, marble, 1868

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edmonia_lewis_minnehaha.jpg

The success and popularity of her work in Boston allowed Lewis to fund a trip to Rome in 1866. On her 1865 passport is written M Edmonia Lewis is a Black girl sent by subscription to Italy having displayed great talents as a sculptor. The established sculptor Hiram Powers gave her space to work in his studio. She entered a circle of expatriate artists and established her own space within the former studio of the 18thcentury Italian sculptor Antonio Canova, just off the Piazza Barberini. Lewis received professional support from both Charlotte Cushman, a Boston actress and a pivotal figure for expatriate sculptors in Rome, and Maria Weston Chapman, a dedicated worker for the anti-slavery cause.

Lewis spent most of her adult career in Rome, where Italy’s less pronounced racism allowed increased opportunity for a Black artist. In Rome Lewis enjoyed more social, spiritual, and artistic freedom than she had had in the United States. Being a Catholic, her experience in Rome also allowed her both spiritual and physical closeness to her faith. In America Lewis would have had to continue relying on abolitionist patronage; but Italy allowed her to make her own way in the international art world

She began sculpting in marble, working within the neoclassical manner, but focusing on naturalism within themes and images relating to Black and American Indian people. The surroundings of the classical world greatly inspired her and influenced her work, in which she recreated the classical art style, presenting people in her sculptures as draped in robes rather than in contemporary clothing.

Lewis was unique in the way she approached sculpting abroad. She insisted on enlarging her clay and wax models in marble herself, rather than hire native Italian sculptors to do it for her, which was the common practice at the time. Male sculptors were largely sceptical of the talent of female sculptors, and often accused them of not doing their own work. Lewis also was known to make sculptures before receiving commissions for them or sent unsolicited works to Boston patrons requesting that they raise funds for materials and shipping.

While in Rome Lewis continued to express her African American and Native American heritage. One of her more famous works Forever Free depicted a powerful image of an African American man and women emerging from the bonds of slavery. Another sculpture Lewis created was called The Arrow Maker, which showed a Native American father teaching his daughter how to make an arrow. Her work sold for large sums. In 1873 an article in the New Orleans Picayune stated “Edmonia Lewis had snared two 50,000-dollar commissions.” Her newfound popularity made her studio a tourist destination and she had many major exhibitions, including one in Chicago, Illinois and in Rome.

During her time in Rome, Edmonia was a member of a circle of fellow expatriate artists, specifically Charlotte Cushman’s circle of women artists, many of whom were lesbian. Although there is no evidence of Edmonia’s sexual orientation, she thrived in this community, which she was forced to leave after developing breast cancer, when she moved to England for treatment.

women in Edmonia’s circle were lesbians, with Charlotte and her partner Emma Stebbins as the head of the pack. For this reason, most historians have concluded that Edmonia must have also engaged in relationships with women. Her proclivity for “men’s clothing” and dressing against 19th century gender norms is just further proof of her involvement in the LGBT social circles in Rome.

Edmonia was forced to leave the community she had found in Rome after finding a lump in her breast. She moved to England for medical treatment.

The Death of Cleopatra

The Death of Cleopatra, Marble, 1876

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Death_of_Cleopatra.JPG#/media/File:The_Death_of_Cleopatra.JPG

A major coup in her career was participating in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

For this, she created a monumental marble sculpture, The Death of Cleopatra. This piece depicts the moment in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra when Cleopatra takes the asp to her breast. The artist J S Ingraham wrote that Cleopatra was the most remarkable piece of sculpture in the American section of the Exposition. Many were

shocked by Lewis’s frank portrayal of death, but the statue drew thousands of viewers. Cleopatra was considered a woman of both sensuous beauty and demonic power, and her self-annihilation has been portrayed numerously in art, literature and cinema. In Death of Cleopatra, Edmonia Lewis added an innovative flair by portraying the Egyptian queen in a dishevelled manner, a departure from the idealised Victorian approach to representing death.

Considering Lewis’s interest in

emancipation imagery as seen in her work Forever Free, it is not surprising that Lewis eliminated

Cleopatra’s usual companion figures of loyal slaves from her work. Lewis’s The Death of Cleopatra may have been a response to the culture of the Centennial Exposition, which celebrated one hundred years of the United States being built around the principles of liberty and freedom, a celebration of unity despite centuries of slavery, the recent Civil War, and the failing attempts and efforts of Reconstruction. In order to avoid any acknowledgement of Black empowerment by the Centennial, Lewis’s sculpture could not have directly addressed the subject of Emancipation. Although her white contemporaries were also sculpting Cleopatra and other comparable subject matter (such as Harriet Hosmer’s Zenobia), Lewis was more prone to scrutiny on the premise of race and gender due to the fact that she, like Cleopatra, was female:

The associations between Cleopatra and a black Africa were so profound that…any depiction of the ancient Egyptian queen had to contend with the issue of her race and the potential expectation of her blackness. Lewis’ white queen gained the aura of historical accuracy through primary research without sacrificing its symbolic links to abolitionism, black Africa, or black diaspora. But what it refused to facilitate was the racial objectification of the artist’s body. Lewis could not so readily become the subject of her own representation if her subject was corporeally white.

After being placed in storage, the statue was moved to the 1878 Chicago Interstate Exposition, where it remained unsold until it was acquired by `Blind John’ Condon, a gambler who purchased it from a saloon on Clark Street to mark the grave of a Racehorse named Cleopatra. The grave was in front of the grandstand of his Harlem race track in the Chicago suburb of Forest Park, where the sculpture remained for nearly a century until the land was bought by the US Postal Service. At this time it was moved to a construction storage yard in Cicero, Illinois where it was damaged. Dr James Orland, a member of the Forest Park Historical Society later acquired the sculpture and held it in private storage at the Forest Park Mall.

Later Career

A testament to Lewis’s renown as an artist came in 1877 when former US President Ulysses S Grant commissioned her for his portrait. She also contributed a bust of Massachusetts abolitionist senator Charles Sumner to the 1895 Atlanta Exposition.

In the late 1880s, neoclassicism declined in popularity, as did the popularity of Lewis’s artwork. She continued sculpting in marble, increasingly creating altarpieces and other works for Catholic patrons. A bust of Christ, created in her Rome studio in 1870, was rediscovered in Scotland in 2015.

.

In 1901 she moved to London. The events of her later years are not known.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/sculptor-edmonia-lewis-shattered-gender-race-expectations-19th-century-america-180972934/

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/edmonia-lewis-2914

https://artuk.org/discover/stories/who-was-edmonia-wildfire-lewis

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/oct/10/feted-forgotten-redeemed-how-edmonia-lewis-made-her-mark

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/lewis-edmonia/

https://www.lbhf.gov.uk/articles/news/2020/09/black-history-month-edmonia-lewis-remarkable-hammersmith-sculptor\

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmonia_Lewis#cite_note-60

https://www.historyisgaypodcast.com/notes/2021/03/22/episode-35-claim-to-flame

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/john-gibson-his-life-rome

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/john-gibson-his-life-rome