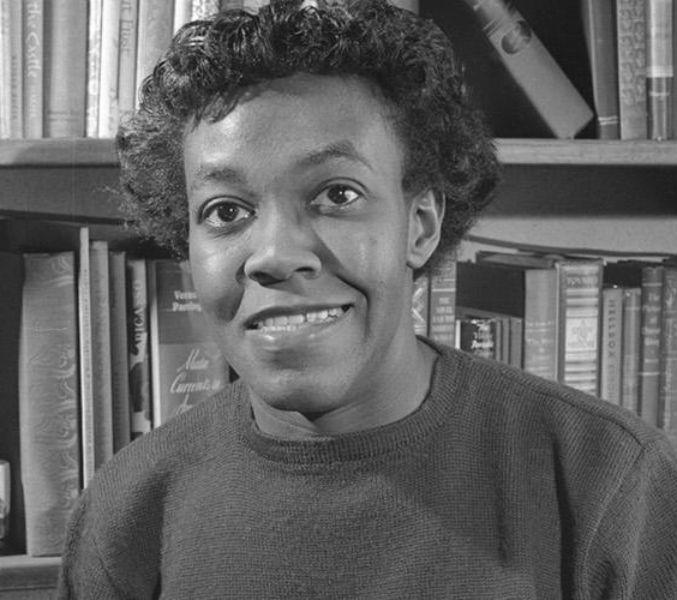

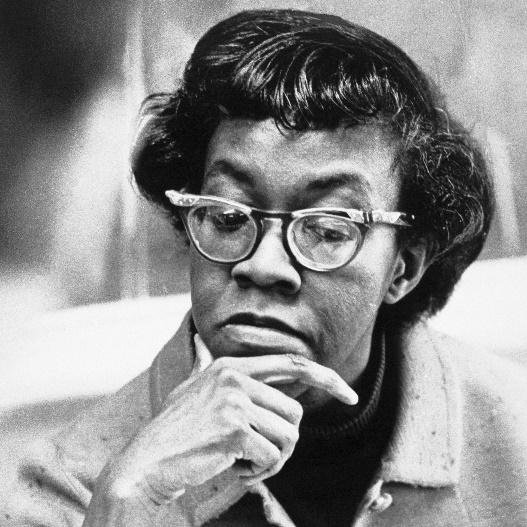

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks

Brooks was an American poet, author, and teacher. Her work often dealt with the personal celebrations and struggles of ordinary people in her community. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry on 1May 1950, for Annie Allen, making her the first African American to receive a Pulitzer Prize.

1917

2000

Topek, Kansas, USA

African American

1946, Guggenheim Fellow in Poetry.

1949, Poetry magazine’s Eunice Tietjens Memorial Prize

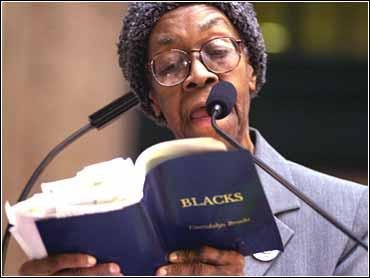

1950, Pulitzer Prize in Poetry Gwendolyn Brooks in 1950 became the first African-American to be given a Pulitzer Prize. It was awarded for the volume, Annie Allen, which chronicled in verse the life of an ordinary Black girl growing up in the Bronzeville neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side.

1968, appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois, a position she held until her death in 2000

1969, Anisfield-Wolf Book Award

1973, Honorary consultant in American letters to the Library of Congress

1976, inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters

1976, the Shelley Memorial Award of the Poetry Society of America

1980, appointed to Presidential Commission on the National Agenda for the Eighties.

1981, Gwendolyn Brooks Junior High School in Harvey, Illinois dedicated in her honor.

1985, selected as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, an honorary one-year term, known as the Poet Laureate of the United States

1988, inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame

1989, awarded the Robert Frost Medal for lifetime achievement by the Poetry Society of America

1994, chosen to present the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Jefferson Lecture

1994, received the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters[32]

1995, presented with the National Medal of Arts

1997, awarded the Order of Lincoln, the highest honour granted by the State of Illinois.

1999, awarded the Academy of American Poets Fellowship for distinguished poetic achievement

She started her formal education at Forestville Elementary School on Chicago’s South Side. Brooks then attended a prestigious integrated high school in the city with a predominantly white student body, Hyde Park High School; transferred to the all-Black Wendell Phillips High School; and finished her schooling at integrated Englewood High School.

According to biographer Kenny Jackson Williams, due to the social dynamics of the various schools, in conjunction with the era in which she attended them, Brooks faced much racial injustice. Over time, this experience helped her understand the prejudice and bias in established systems and dominant institutions, not only in her own surroundings but in every relevant American mind set.

Brooks began writing at an early age and her mother encouraged her, saying, “You are going to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar.” During her teenage years, she began filling books with `careful rhymes, and ‘lofty meditations,’ as well as submitting poems to various publications. Her first poem was published in American Childhood when she was 13. By the time she had graduated from high school in 1935, she was already a regular contributor to The Chicago Defender.

After her early educational experiences, Brooks did not pursue a four-year college degree because she knew she wanted to be a writer and considered it unnecessary. “I am not a scholar,” she later said. “I’m just a writer who loves to write and will always write.” She graduated in 1936 from a two-year program at Wilson Junior College, now known as Kennedy-King College, and worked as a typist to support herself while she pursued her career.

Brooks published her first poem Eventide, in a children’s magazine, American Childhood, when she was 13 years old. By the age of 16, she had already written and published approximately 75 poems. At 17, she started submitting her work to Lights and Shadows, the poetry column of the Chicago Defender, an African American newspaper. Her poems, many published while she attended Wilson Junior College, ranged in style from traditional ballads and sonnets to poems using blues rhythms in free verse. In her early years, she received commendations on her poetic work and encouragement from James Weldon Johnson, Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. James Weldon Johnson sent her the first critique of her poems when she was only sixteen years old.

Her characters were often drawn from the inner city life that Brooks knew well. She said, “I lived in a small second-floor apartment at the corner, and I could look first on one side and then the other. There was my material.”

By 1941, Brooks was taking part in poetry workshops. A particularly influential one was organized by Inez Cunningham Stark, an affluent white woman with a strong literary background. Stark offered writing workshops at the new South Side Community Art Centre, which Brooks attended. It was here she gained momentum in finding her voice and a deeper knowledge of the techniques of her predecessors. Renowned poet Langston Hughes stopped by the workshop and heard her read The Ballad of Pearl May Lee. In 1944, she achieved a goal she had been pursuing through continued unsolicited submissions since she was 14 years old when two of her poems were published in Poetry magazine’s November issue. In the autobiographical information she provided to the magazine, she described her occupation as a `housewife’.

Brooks’ published her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), with Harper & Brothers, after a strong show of support to the publisher from author Richard Wright. He is quoted as saying to the editors who solicited his opinion on Brooks’ work that

“There is no self-pity here, not a striving for effects. She takes hold of reality as it is and renders it faithfully. … She easily catches the pathos of petty destinies; the whimper of the wounded; the tiny accidents that plague the lives of the desperately poor, and the problem of colour prejudice among Negroes.”

The book earned instant critical acclaim for its authentic and textured portraits of life in Bronzeville. Brooks later said it was a glowing review by Paul Engle in the Chicago Tribune that initiated her reputation. Engle stated that Brooks’ poems were no more `Negro poetry’ than Robert Frost’s work was `white poetry’. Brooks received her first Guggenheim Fellowship in 1946 and was included as one of the Ten Young Women of the Year in Mademoiselle magazine.

Brooks’ second book of poetry, Annie Allen (1949), focused on the life and experiences of a young Black girl growing into womanhood in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. The book was awarded the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, and was also awarded Poetry magazine’s Eunice Tietjens Prize.

In 1953, Brooks published her first and only narrative book, a novella titled Maud Martha, which in a series of 34 vignettes follows the life of a Black woman named Maud Martha Brown as she moves about life from childhood to adulthood. It tells the story of a woman with doubts about herself and where and how she fits into the world. “Maud’s concern is not so much that she is inferior but that she is perceived as being ugly,” states author Harry B Shaw in his book Gwendolyn Brooks. Maud suffers prejudice and discrimination not only from white individuals but also from Black individuals who have lighter skin tones than hers, something that is a direct reference to Brooks’ personal experience. Eventually, Maud stands up for herself by turning her back on a patronising and racist store clerk. “The book is … about the triumph of the lowly,” Shaw comments. In contrast, literary scholar Mary Helen Washington emphasises Brooks’s critique of racism and sexism, calling Maud Martha “a novel about bitterness, rage, self-hatred, and the silence that results from suppressed anger”.

In 1967, the year of Langston Hughes’s death, Brooks attended the Second Black Writers’ Conference at Nashville’s Fisk University. Here, according to one version of events, she met activists and artists such as Imamu Amiri Baraka, Don L Lee and others who exposed her to new Black cultural nationalism. Recent studies argue that she had been involved in leftist politics in Chicago for many years and, under the pressures of McCarthyism, adopted a Black nationalist posture as a means of distancing herself from her prior political connections. Brooks’ experience at the conference inspired many of her subsequent literary activities. She taught creative writing to some of Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers, otherwise a violent criminal gang. In 1968, she published one of her most famous works, In the Mecca, a long poem about a mother’s search for her lost child in a Chicago apartment building. The poem was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry.

Her autobiographical Report From Part One, including reminiscences, interviews, photographs and vignettes, came out in 1972, and Report From Part Two was published in 1995, when she was almost 80.

Parents: Keziah Wims, David Anderson Brooks

Spouse: Henry Blakely (married 1973–1996

Children: Nora Brooks Blakely, Henry Lowington Blakely III, Nora Blakely

Siblings: Raymond Brooks

https://lambdaliterary.org/2017/06/notes-for-a-prospective-biographer-snapshots-and-remembrances-on-gwendolyn-brooks-hundredth-birthday/ accessed 17/04/2022

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/chicagos-particular-cultural-scene-and-the-radical-legacy-of-gwendolyn-brooks accessed 17/04/2022

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/poet-gwendolyn-brooks-has-died/ accessed 17/04/2022

https://www.Blackpast.org/african-american-history/brooks-gwendolyn-1917/ accessed 17/04/2022

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gwendolyn_Brooks accessed 17/04/2022

https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/25128.Gwendolyn_Brooks accessed 17/04/2022