Paul Leroy Robeson

Jeff Sparrow summarised Paul Robeson as a man who ‘possessed one of the most beautiful voices of the 20th century. He was an acclaimed stage actor. He could sing in more than 20 different languages; he held a law degree; he won prizes for oratory. He was widely acknowledged as the greatest American footballer of his generation. But he was also a political activist, who, in the 1930s and 1940s, exerted an influence comparable to Martin Luther King and Malcolm X in a later era.’ Robeson had a great bond with the labour movement and especially with Welsh miners, a relationship some claim to have shaped Robson’s politics. “It’s from the miners in Wales,” Robeson explained, “[that] I first understood the struggle of Negro and white together.”

9/11/1898

23/01/1976

Princeton, New Jersey, USA

African American

1915- Wins a four year scholarship to Rutgers University

1919- Make the All American football team in Yale

1922- Cast as Jim in the play Taboo by Mary Hoyt Wiborg; he postponed studies so he could take part in this

1924- Plays lead role in All God’s Chillun Got Wings

1925- Starred in the London production of The Emperor Jones by Eugene O’Neil

– Appeared in his first film Body and Soul

1928- Starred in London production of Show Boat

1930- Starred in Othello in London

1943- Starred in Othello in Broadway 1943 and won great praise. The show ran for 296 performances, which set an all-time record for the run of a Shakespearean play in Broadway history.

1924-1942- Robeson starred in 11 films including Jericho 1937 and Proud Valley 1939

1984 Received the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People) Image Award

1998 Robeson was awarded with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award

-He was inducted posthumously into the College Football Hall of Fame

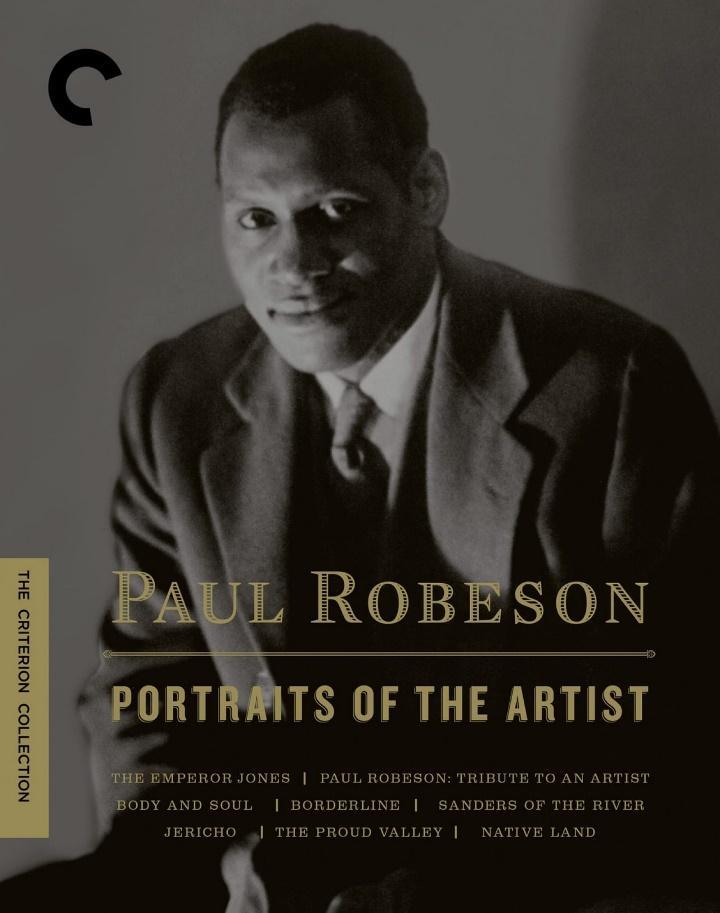

2007 – Criterion released Paul Robeson: Portraits of the Artist, a box set containing several of his films, as well as a documentary and booklet on his life.

Robeson’s mother was Anna Louisa Bustil and came from an abolitionist Quaker family. His father was William Drew Robeson who was born into slavery and escaped from a plantation in his teens. He lost his mother at the early age of six when she died in a fire, and he moved with his father to Somerville. It was here Robeson began to excel both academically and in singing at church. He earned a scholarship to attend Rutgers University and was the third African American to do so. During his time there he became one of Rutgers’ most decorated students, receiving top honours for his debate and oratory skills, winning 15 letters in four varsity sports, was elected Phi Beta Kappa, and became class valedictorian.

Robeson then attended Columbia University Law School from 1919-1923. To pay his tuition he would teach Latin and play pro football.

Robeson had a varied career and excelled in many areas. His political activism had a great impact amongst Welsh mining towns after the 1926 General Strike.

Athletics:

Robeson was scouted and recruited by Fritz Pollard to play for the NFL’s Akron Pros, which he did as he completed his law studies. He ended his football career in 1922.

Lawyer:

Robeson worked briefly as a lawyer in 1923 , however he faced widespread racism and disrespect, particularly when his white secretary refused to take instruction off him and he left the firm and the practice of law.

Actor:

-In Spring 1922, Robeson was cast as Jim in the play Taboo by Mary Hoyt Wiborg; he postponed studies so he could partake in this.

-He continued to land acting and singing gigs in plays, including the OffBroadway production of Shuffle Along and then Taboo in Britain which was later adapted to highlight his singing.

-A more controversial production Robeson took part in was the 1924 All God Chillun Got Wings In New York.

-In 1925 he starred in the London production of The Emperor Jones by Eugene O’Neil. During this year he also entered the realm of film with his appearance in Body and Soul, directed by Oscar Micheaux.

-Robeson was involved in the 1928 London production of Show Boat, this is where he first sang Ol’ Man River, a song destined to become his signature tune.

-Robeson’s role in the production of Othello in London 1930 and Broadway 1943 won great praise. The show ran for 296 performances which set an all-time record run for a Shakespearean play in Broadway history.

-He starred in 11 films which included Body and Soul, 1924, Jericho 1937 and Proud Valley 1939. His last movie was the Hollywood production of Tales of Manhattan 1942, which he criticised for its demeaning portrayal of African Americans.

Singer:

Robeson frequently sang in his deep baritone voice to promote Black spirituals to benefit labour and social movements of his time. He sang for peace and justice in 25 languages throughout the USA, Europe, Africa and the USSR.

Details of the most important achievements, titles and dates of any works; appointment to significant posts/offices:

Political Activism

Throughout his lifetime, Robeson frequently spoke out against racial injustice and was involved in world politics. Supporting Pan Africanism, singing for Loyalist soldiers during the Spanish Civil War , partaking in anti-Nazi demonstrations – these are just a few examples of his political activism.

Interaction with USSR

Robeson protested against the Cold War and worked hard to bridge friendship between the USA and the USSR. However, his relationship with the USSR faced scrutiny for the conflict of his humanitarian beliefs with Stalin’s sanctioned terror and mass killing regimes. Robeson’s relationship with USSR and a misrepresentation of the speech he made at the Paris Peace Conference in the late 1940s saw him labelled as a communist and fiercely criticised. This led to him being barred from renewing his passport and being blacklisted from many domestic venues, recording labels and film studios.

Robeson and the Welsh Miners

Robeson accidentally encountered a party of Welsh miners from Rhondda after their perfect harmonies caught his attention. They had been blacklisted by their employers after the General Strike of 1926 and had walked all the way to London in desperate measures to find ways to feed their families. Robeson joined their march without hesitation. He remained with the protestors and when they stopped he sang Ol’ Man River and a selection of spirituals chosen by the miners. After the protests he gave the miners a generous donation, allowing them to return by train with plenty of food and clothing. He continued to support the Welsh miners, contributing the proceeds of a concert to the Welsh miners’ relief fund. During his tour he frequently dedicated songs to the miners and their families in Cardiff, Aberdare and Neath. He also visited the Talygarn Miners rest home in Pontyclun. He continued to visit Welsh mining towns and, at a time when they suffered immensely and felt hopeless, his connection brought much light. Robeson’s legacy amongst Welsh mining towns remains and has been celebrated; for example, the Robeson exhibition in Pontypridd in 2001 and October 2015.

-1984- Awarded with the NAACP Image Award

-1998 Robeson was awarded with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award

-He was inducted posthumously into the College Football Hall of Fame

-In 2007, Criterion released Paul Robeson: Portraits of the Artist, a box set containing several of his films, as well as a documentary and booklet on his life

Robeson married Eslanda Cordoza Goode, a fellow student at Columbia Law School. . They were married for more than 40 years and had a son Paul Robeson Jr. Eslanda was also inspiring as she became the first Black woman to head a pathology laboratory.

After taking a likening to the USSR’s folk culture Robeson and his family began learning Russian and then came to reside in Moscow.

When Robeson’s career was damaged after his relationship with the USSR he suffered debilitating depression and related health problems. He and his family returned to the USA in 1963. He then died from a stroke on January 1976 in Philadelphia.

To read more about Robeson and Wales read:

Martin Alan Rhodes, ‘Exhibiting memory: Temporary, mobile, and participatory memorialization and the Let Paul Robeson Sing! Exhibition’, Sage Journals, 13.6 (2018) 1235-1255.

Martin Alan Rhodes, “They feel me a part of that land”: Welsh memorial landscapes of Paul Robeson (Kent: Kent State University, 2015)

For a detailed account of Robeson’s life read:

-Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography (New York : Open Road Media, 2014)

-Criterion, ‘Paul Robeson: Portraits of the Artist’, The Criterion Collection (Criterion, revised 2007) <https://www.criterion.com/boxsets/443-paul-robeson-portraits-of-the-artist > [accessed 17 February 2022]

-Robeson’s autobiography 🡪 Paul Robeson, Here I Stand (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958)

Credits (where info sourced from)

-Martin Duberman, Paul Robeson: A Biography (New York :Open Road Media, 2014)

-Martin Alan Rhodes, ‘Exhibiting memory: Temporary, mobile, and participatory memorialization and the Let Paul Robeson Sing! Exhibition’, Sage Journals, 13.6 (2018) 1235-1255.

-Philip S. Forner, Paul Robeson Speaks-Writings, Speeches, Interviews 1918-1947 (New York: Brunner-Mazel Publishers, 1978)

-Jeff Sparrow, ‘’, The Observer biography books (The Guardian, revised 2017) < https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jul/02/how-paul-robeson-found-political-voice-in-welsh-valleys#:~:text=%E2%80%9CIt’s%20from%20the%20miners%20in,of%20Negro%20and%20white%20together.%E2%80%9D > [accessed 17 February 2022]

-Criterion, ‘Paul Robeson: Portraits of the Artist’, The Criterion Collection (Criterion, revised 2007) <https://www.criterion.com/boxsets/443-paul-robeson-portraits-of-the-artist > [accessed 17 February 2022]